There are some important differences between public and private breeding – and how these differences affect seed growers and crop farmers is often a matter of hot debate in Canada.

Until the 1990s, seed development in Canada was primarily public, and continuing public crop breeding still provides a high return on investment, according to Dr. Rob Graf, a winter wheat breeder at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta. Indeed, it’s been estimated that every dollar invested in public cereals breeding provides at least 20 times the return in the form of better crops, spin-off industry jobs, check off investments in additional research and so on. With private-bred seed, many argue most of the profits often go to company shareholders who may not even be Canadian.

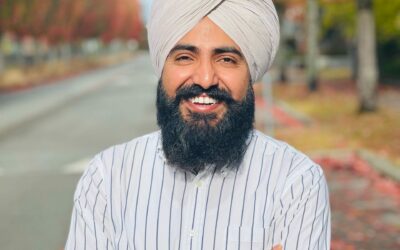

Dr. Stephen Morgan Jones agrees that private plant breeding is conducted to make a profit. “Public plant breeding is primarily carried out to produce improved varieties with the adoption of the new variety being more important than the return on investment,” explains the owner of Lethbridge-based consulting firm Amaethon Agricultural Solutions. “There is also a general feeling that private breeding programs, such as the ones for canola, soybean and corn, are very well capitalized, with excellent equipment and other resources, whereas public breeding programs tend to generally have resource issues.”

It is also a perception among many in the crop sector that, high return on investment or not, Canada’s public breeding efforts when it comes to cereal varieties have been dismal – amongst the lowest yielding in the world. Graf disagrees and points out that the rate of yield increase for wheat in Western Canada compares favourably with other parts of the world and that average yields are trending upwards. It is also clear, he says, that public cultivars are very popular with western Canadian farmers. Public wheat breeding is wholly directed towards finished cultivars that are vital to the industry, and Graf says that while public breeders have been very effective in increasing yield, productivity traits and disease resistance through long-term, stable breeding programs, there is also ample room for private sector involvement. “Both sectors are focused on industry sustainability,” he says, “but the way it’s looked at may be somewhat different.”

Morgan Jones notes wheat producers are very much already involved in partnerships with public plant breeding, with millions of producer dollars invested in it on an ongoing basis through the wheat check-off. He also points out that the Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF) and the wheat commissions (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) have developed long-term partnerships with universities and government, and these arrangements often include the sharing of royalty revenue from producer-supported varieties. Like Graf, he notes there are some 4-P arrangements (public/private/producer partnerships) already in place, and that these could be enhanced. (See article in this issue with updates on a very successful Canadian 4-P partnership.)

Cost and Risk

Some crop farmers have concerns about the present cost of private-bred seed and that those costs will only rise. The cost of private-bred canola is certainly high, but farmers have found that with this crop, a good profit is still achievable due to factors like high yield and strong market demand. However, some farmers wonder if the same situation will occur with cereals.

Morgan Jones says although Syngenta has been involved in wheat breeding in Western Canada for many years, and other companies such as Bayer and Canterra Seeds have recently begun investing in it, companies have rightly had concerns about recovering costs.

“For large acreage crops such as CWRS [Canada Western Red Spring] wheat, there is a sufficiently large seed market to justify investment,” he says. “But if you compare the economics for wheat and canola, with wheat seed planted at about 20 times the rate of canola seed, there is the issue of handling quite a large amount of seed and producing it in a way that makes any profit viable. There is thus little interest in cereal crops with less than five million acres.”

Morgan Jones acknowledges that private company development of proprietary traits such as herbicide or insect resistance requires a large investment and that this ultimately results in higher seed prices. On the other hand, public breeders, in most cases, take a royalty on the future sales of their variety by the seed company, but the royalty is usually less than five per cent of the seed price.

“This means that private companies will tend to focus on traits that have an immediate positive impact on farmer profit, such as increased yield and lower input costs or lower cost production systems,” he says. “In contrast, public investment in plant breeding tends to be for the longer term, with more attention given to finding new sources of disease and insect resistance, and maintaining and improving wheat quality.”

Morgan Jones also points out that while private companies dominate the canola seed market, there is still a large public investment in canola genomics, pre-breeding new lines and sources of disease resistance. “I think it’s important to have a balance of public and private investment,” he notes.

However, in his view, this does not apply in cases where there are multiple private companies competing to provide similar seed that meet farmers’ needs.

“In that situation, there is little justification to continue public investment in variety development, and public investment is better to shift to a more basic, longer-term approach to ensure the genetic variability is available for the future,” Morgan Jones says. “At the same time, there is no doubt that using current methodology, the current private focus of developing hybrid wheat varieties will be more expensive to produce and market, and the extra performance will have to be very evident for farmers to be motivated to spend more on the seed.”

Moving Forward

In terms of how private and public wheat breeding will play out in the coming years, Graf would like to see germplasm exchange encouraged and simplified.

“Germplasm is the ‘life-blood’ of plant breeding, and if we are to meet the challenging requirements of the future, we need to work together, building on each other’s successes,” he says.

Morgan Jones notes breeders have a voluntary code of practice promoting ethical behaviour, and though the code does include exchange between public and private breeders, he suspects this is limited to certain material only.

“For germplasm exchange to work effectively, it requires breeders who receive material to reciprocate with others,” he says. “Some universities in the U.S. strictly control their germplasm and want a share of any future revenues that may result from their germplasm being used in future crosses. This tends to limit exchange of germplasm. In the case of wheat in Canada, the best germplasm is currently held by public plant breeders, although this may change in the longer term as private companies invest more in wheat.”

Graf also believes the current strong, transparent and merit-based registration system should continue, with its balanced approach to sector requirements that include disease and pest resistance. He says it works for the benefit of the entire industry and it encourages quick uptake of new cultivars because there is less risk to the entire value chain, from the pedigreed seed producer to the commercial farmer and end-use customer.

Morgan Jones, however, thinks the current process of government-controlled variety registration adds years to the time a new variety could be released to the industry. He suggests the possibility of a hybrid registration system, where a producer could get very early access to advanced breeder lines in which traits were reliably expressed, and work with a grain company to commercially test them. The farmer and grain company would jointly take the risk and in some cases the breeding line would be rejected, but the ones that were successful would likely be able to be commercialized two to three years sooner.

“I would argue that food safety is the role for government and that the industry itself should be mature enough to manage quality as is the case in other commodities,” Morgan Jones notes.

Whatever the future holds, Graf believes there will always be a need for public breeding. For example, he says there has been little private interest in developing new durum varieties, minor spring wheat classes or winter wheat, so public breeding of these classes will therefore need to continue if the industry sees value in Canadian production of these commodities.